THE FOLDED FLOCK

I have the privilege of being the custodian of a superb flock of Hampshire Downs and lambing is currently well under way. The flock was established in the late 19th Century by my great grandfather and has grazed the downs here ever since. At one time, there were over 3000 breeding ewes on the Estate with 14 shepherds to care for them! Today the pedigree flock consists of around 160 ewes.

The breed was incredibly popular in its heyday; my great grandfather achieving an average price of 23 guineas for a run of 100 ram lambs at Wilton Sheep Fair before the 1st World War. Cull ewes would make more than £5 each, and this in the days when a man was paid 7 shillings and 6 pence per week. The flock was managed according to the principles of forward ‘creep’ grazing. This achieved by the use of enclosed areas, secured by hurdles, known as ‘folds’. The flock was ‘folded’ across fields of root crops (brassicas) in the winter and Vetches and Sainfoin in the summer.

In a thick crop, the fold would be made of 25 by 25 hurdles, allowing 4 sheep per hurdle, thus 200 sheep in the fold. A thinner crop would have a fold of 30 by 30 hurdles. Hurdles were secured by a ‘shore’; a hazel post driven and then hit into a hole made by a shepherd’s bar and then secured by a coil of hazel known as a ‘shackle’.

Two of our newest Hampshire Downs, captured by resident artist Sally Newton.

Folding, if it were affordable, would be the best way to manage sheep in this part of the country. They eat the crop in its entirety, wasting nothing and cover the ground with a layer of droppings. The main flock was retained in the fold for one day but the lambs had access to the next fold via a ‘creep’; a metal barrier with bars, placed in the middle of the hurdle fence between the old fold and the new. In the meantime, a new fold would be constructed above the one containing the lambs. On the following day, the ewes would be allowed into the fold which the lambs had grazed and the lambs could the access the fold that had just been built.

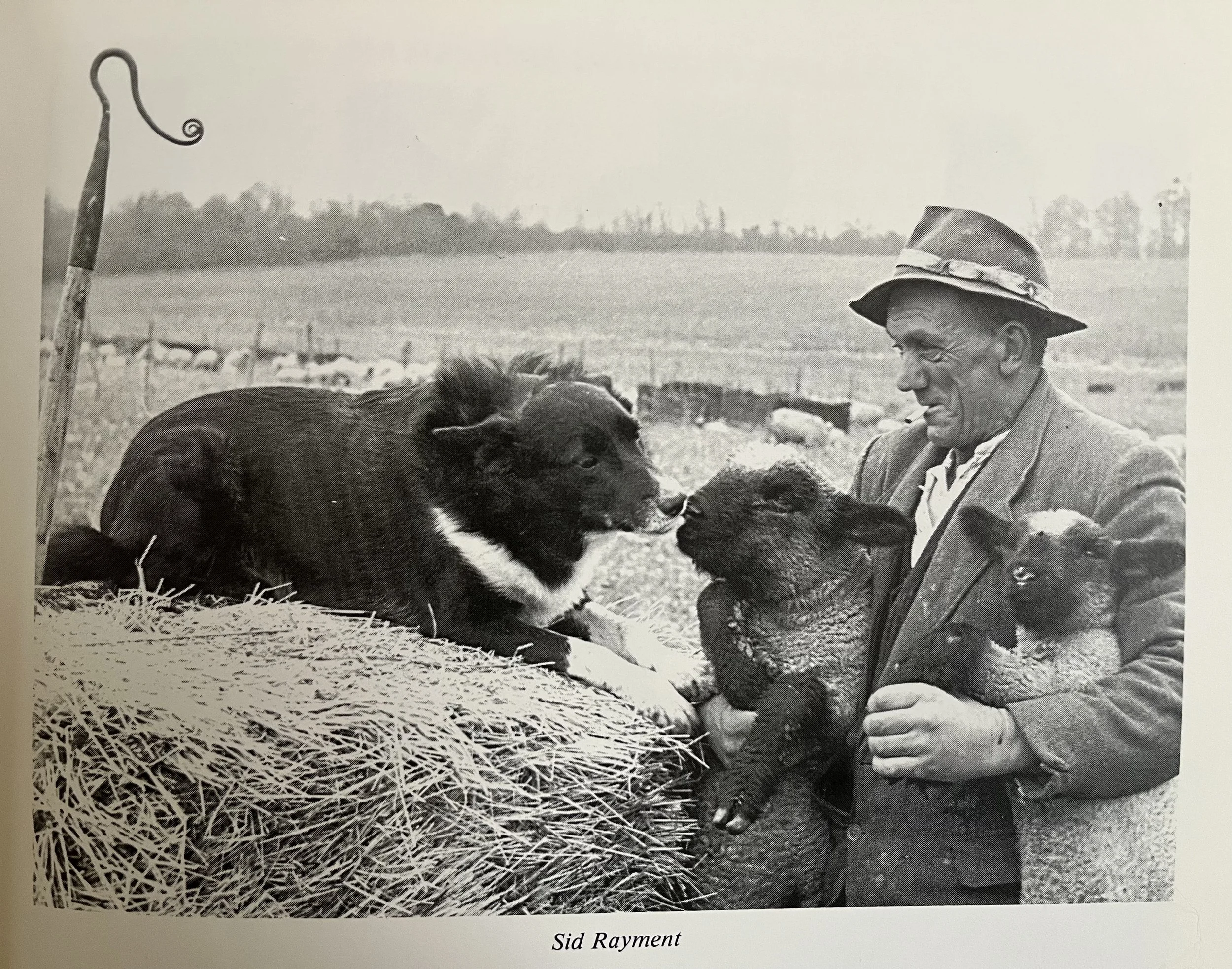

The last Master Shepherd on the estate was Sid Rayment. A most endearing man with a face, tanned and leathery, deeply fissured, torn by winter squalls, and spring hail, and yet locked in an expression of permanent benevolence and joviality. Born in Dorset, he spoke with a soft Dorset burr and like his Father and Grandfather before him, was an exclusive Hampshire Down shepherd. Not for him “them other dratted things”, for a dog only “Old English Bobtail” would do. “They others, them’s too fast”.

Our last Master Shepherd, Sid Rayment with Hampshire Down lambs

Lambing was then conducted in an elaborate rectangular pen with small cubicles around its periphery made of hurdles and partially thatched with straw. This was placed in the middle of an open field, and was always, absolutely freezing. Sid lived in a Shepherd’s Hut drawn up close to the pen (if you are familiar with the estate, you will have seen his blue hut now parked in the farmyard!) and there he stayed until the lambing was over. His wife, Pearl, would bring him provisions every day while he cared for his stock throughout.

The Shepherd’s Hut where Sid Rayment lived during lambing, now in our farmyard.

The hut, squat with blue oxide timber sides, always seemed to have a lazy coil of smoke oozing from its ancient chimney, as bacon was fried and coffee brewed on the cast iron stove in its corner. Sid slept on a bunk. I can see him now leaning on a hurdle, with a piercing frost and 6 inches of snow on the ground, gently toying with a rolled up cigarette in the calloused fingers of his right hand. My father, rather portly and known as The Captain, with a steaming pipe in hand is speaking to him. “How’s it going then shepherd?” and Sid replies “The water carts froze but the lambs is good Capt’n but they ewes want some better hay and the turnips is a bit thin. The boy and I will pitch the hurdles this afternoon and move ‘em on”.

My father always considered the shepherd the most important man on the place and his requirements for his sheep were the rule of law. Sid worked 7 days a week and always wore a round felt brimmed pork pie hat, black with sheep’s grease and an army great coat with leather spats and boots to protect his legs. He carried a holly crook, “ollie’s the best” he would tell me. He carried a ‘lightning stone’ in his pocket, an echinoid fossil found on the down, which would protect him from thunder strike if he was caught in a storm. He would accept no overtime and took his holidays travelling around the country showing his sheep. With a comb and a pair of shears, he had no equal, turning rough fleeces into an immaculate trim and pairing up animals so they would appear to be twins.

Sid, as well as being probably the last of the great downland shepherds, also had a sharp wit, never at a loss to find a humorous touch to every situation. He was an expert in bell ringing and would listen and describe peels from all over the country.

When he was in his 80’s, he was struck down with pneumonia and had to go to hospital, a complete novelty for him. Visiting him, he told me “I'm fed up with them fussing o’er me, all I wants is to be back with my sheep”. He was taken later that week and I have no doubt that somewhere on those Elysium hills, he is still looking after his sheep with the same unremitting care, through snow and tempest that he demonstrated through his long and remarkable life.

words by Henry Edmunds F.R.E.S.